This article shares the experiences of FET teachers who were forced, in many cases reluctantly, to engage in a process that transformed their perspectives on themselves, personally and professionally, and fundamentally changed their relationships with their teaching colleagues. It shares some understanding of the variables that influence how FET teachers perceive themselves: identities, work roles, professional learning and development, and the relation between all three.

Having a commitment to lifelong learning is essential to the professional development of teachers as adaptable, self-reliant educators (Coolahan, 2002). And it is vital for further education and training (FET) teachers, whose expertise in vocational areas must support flexible responses to evolving industry practices, standards, and expectations.

Traditionally, FET is less structured than primary, post-primary, or third-level systems, and FET teachers take pride in the fact that they do things differently. They tend to have had previous careers outside of academia and consequently are inclined to have a more practical, applied approach. This resonates with those who have felt excluded by the mainstream education system.

Often referred to as the ‘Cinderella’ of Irish Education, the FET sector is perceived as ‘different’ and ‘other’. In recent years there has been significant structural and organisational change in addition to the formation of an FET strategy and the changes that QQI has brought to the sector. These have caused shifts in identity, ethos, and objectives for teachers as FET develops from a fractured history to formal recognition in the education sector.

Amendment to FE teacher registration and approved education qualification with the Teaching Council destabilised many working in the sector, creating concern about their (informal) professional status. The chief concerns identified include threats to continuity of employment, career progression, and professional membership of the Teaching Council. The move to professionalise the sector was viewed as putting further barriers into a world of work that was already perceived as unstable and unpredictable, with limited opportunities for progression. FET teachers were working in what might be termed the gig economy of post-compulsory education.

This article shares the experiences of FET teachers who were forced, in many cases reluctantly, to engage in a process that transformed their perspectives on themselves, personally and professionally, and fundamentally changed their relationships with their teaching colleagues.

Insights are provided from a study of two FE teacher qualification programmes – among the first with professional accreditation from the Teaching Council – into how teacher education qualification (TEQ) programmes could best meet the emerging needs of participating teachers, who face some of the most pressing demands in Irish society today. Two subsequent studies (funded by SCoTENS) confirmed these findings.

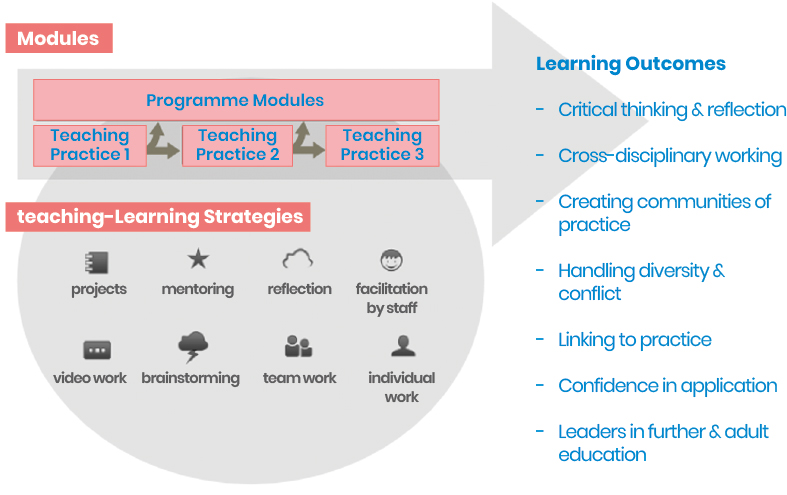

In general, both of these TEQ programmes are designed specifically for FET teaching and learning contexts. They encourage application and facilitate critical reflection, collaborative in-class discussion, group projects, and online threaded discussions. A separate teaching practice (TP) development course usually forms an integral part of the TEQ programme, focused on pedagogical training and curriculum development and design. TP programme assessment usually comprises, per semester, a teaching portfolio, structured reflective assignments, and a TP tutor observation of students during a teaching placement or at the organisation where they are employed as teachers.

Figure 1: Conceptual map of the FET TEQ programme (Graham Cagney, 2019)

Participants reflect the complexity and diversity of the sector. In general, they have prior knowledge and previous teaching experience, often across several disciplines and subjects. Age profiles vary from early 30s to late 50s. Many have worked in other professions and bring that experience to their teaching role. Their employment contracts and roles include voluntary, part-time, and full-time contracts of indefinite duration, and tenured and permanent positions. On graduation, they are entitled to register as FE teachers with the Teaching Council.

Research on enhancing teaching and learning in undergraduate programmes (Entwistle, 2003) suggests that students’ perceptions of their learning environment are strongly determined by a set of overlapping contexts that comprise four elements: course contexts, teaching and assessing content, staff–student relationships, and aspects of the students and student culture in a particular programme (ibid.). This conceptual map of the inner teaching–learning environment (TLE) operates like an organising framework when considering how to achieve a higher quality of learning through the creation of transformative learning spaces.

Participants’ responses show that three areas had most influence on their learning experiences: staff–student relationships, teaching and assessing content, and students and student cultures. Firstly, the affective quality of the relationships between staff and participants, combined with guidance and support for learning, were critical elements in creating a transformative learning space. Providing emotional, psychological, physical, and educational assistance when needed was the foundation on which trusted relationships were built. For one learner, who had a particularly negative experience as a university undergraduate, the quality of her relationship with faculty was significant: ‘Engaging with the lecturers over the year has been really, really huge for me.’

Secondly, critical-thinking assignments, when combined with class discussion that focused on discourse and profound debate, provided the learning space to challenge changes in values and attitudes and to develop the skills of reflective judgement. Some individuals identified a reluctance to engage with critical reflection and writing their thoughts. Others experienced a profound change in their thinking: ‘I spend most of my time now thinking about thinking, than I spend thinking about doing, or even just doing for that matter; this is a fundamental shift for me.’

Providing an immersive experience in a programme enabled students to network, work together, socialise, communicate, and share knowledge and experiences. Another participant said, ‘There’s something fantastic. We used to look forward to it. Who looks forward to going into class?’ Expectations of the programme content, even for some experienced teachers, were very much related to the teaching task. One said: ‘I wanted the “right” answer. I think I was very much in the mode that I was going to be told what to do here, rather than I actually need to trust myself to know what to do.’ Another described her expectations: ‘I had an assumption that someone is going to show me how to be a teacher. Show me the magic book. And there is no magic book.’

[ctt template=”2″ link=”LfluP” via=”no” ]For one learner… the quality of her relationship with faculty was significant: ‘Engaging with the lecturers over the year has been really, really huge for me.[/ctt]

Thirdly, a highly supportive peer group, with embedded norms and values derived from similar work experiences, emerged as a key requirement for developing a transformative space of learning. In considering the impact of other students and student culture, the universal view was that it comprised not only fellow students or classmates but also in some instances work colleagues and their own students or adult learners. One participant said, ‘A community of practice, you don’t have to even explain what you’re talking about. You just mention something and heads nod, people understand what you’re talking about. There’s an unconscious, a collective unconscious.’

When the above three elements occurred in the overlapping contexts of the inner TLE of the TEQ programme, they created a transformative learning space for the participating FET teachers. This may explain the high level of reported experiences of changed perspectives that led to an evolving identity for FET teachers on these programmes.

This type of learning is more than just adding to what someone already knows. It is transformative because it shapes them in ways that result in changes that both they and others around them can now recognise. Perspective transformation is about change: dramatic, fundamental change in how people perceive themselves and the world. Described as ‘a shift of consciousness that dramatically and permanently alters our way of being in the world’ (O’Sullivan et al., 2002, p. xviii), it changes how we know (Kegan, 2009), and it leads to a more ‘inclusive, discriminating, permeable, and integrative perspective’ (Mezirow, 1991, p. 14).

Developing self-confidence and testing new ways of going forward as part of the learning experiences featured for many participants. One teacher reported, ‘Some of the girls in work said that I’ve grown a backbone [laughs]. So I think that was good. I don’t know which comes first, the change, but definitely, both have changed, professionally and personally.’

Very experienced FET teachers also expressed a sense of being professional in a way they had not been before: ‘I suppose a more professional approach to what I’m doing and also more confidence in what I’m doing.’ For others, eligibility to register with the Teaching Council represented formal recognition: ‘The TEQ qualification was the big thing. … No, it was the Teaching Council thing, because of the politics that’s around that.’ Some said their self-confidence and sense of self were enhanced:

I’m really enjoying it and delighted to get the opportunity to get a teaching qualification. Because, definitely for me, well, I am hoping it will validate what I do and hopefully make you a little more than – what did they used to call it? – the ‘woolly jumper brigade’, to actually have a qualification to back up what we do.

Others reported awareness of changes in their values, expectations, and beliefs, particularly about teaching and being an FET teacher. Some were working in the sector part-time but not really committed to it as a career, but this changed over time: they realised it was their career of choice. Changes in thinking that lead to new perspectives on people’s personal and professional lives inform current debate on evolving professional identity and teacher agency in professional learning and development.

Identity self-states draw on a framework of ‘motivational self-systems’ that incorporates ‘possible’ and ‘ideal’ selves theory. Possible selves are ‘ideas which an individual has regarding what they could become (hoped-for self), what they would like to become (ideal self) and what they are afraid of becoming (feared self)’ (Markus and Nurius, 1986, p. 954). These can include multiple possible selves, including more than one ideal self. Possible and ideal self-states have a simultaneous impact on how one engages and expresses oneself in task behaviours that promote connections to work, others, personal presence, and job role performance.

In an educational context, which self-state someone is motivated towards will involve a desire to reduce the discrepancy between one’s actual self and the projected behavioural standards of the ideal or ‘ought’ self. Such a discrepancy would imply that future self-states provide incentive, direction, and impetus for action. Learners who encounter and draw on different spaces of learning are more self-determined in their learning and more willing to engage in new and multiple spaces of learning.

[ctt template=”2″ link=”B3398″ via=”no” ]Very experienced FET teachers expressed a sense of being professional in a way they had not been before.[/ctt]

Most participants described changes in predominantly three areas: knowledge, self-concept, and social norms and cultural expectations (including roles in society). One identified shifts and changes in all three areas simultaneously:

Through learning and studying on the courses I have been able to apply new knowledge to my teaching and learning and have also been able to use my newfound language, words, discourse to open up dialogues with my work colleagues on issues within a disadvantaged community that I think needs to change. I have found that once you can speak like your oppressors [laughs], educated colleagues, they take more notice of what you have to say.

Other participants focused almost entirely on the knowledge they had gained and how this changed their self-concept, with a resulting impact on their identity self-state, moving from fear to confidence. They reported that critical reflection affected the development of their identity self-states, particularly their future selves. Some said they engaged in ‘reflection for action’ or future-orientated reflection on their teacher (ideal self) roles, to visualise the kind of teacher they wanted to become: ‘How I describe myself is changing. My confidence in my identity is growing. I am enjoying trying out the name “teacher” and also reclaiming “student”.’ Some shared ideas on what they could become or would like to become, confirming that their professional identity was evolving:

I think it probably was towards the end of it, and having discussions with some friends of mine who are teachers, and realising that while I would have agreed with them in the past, that my worldview was so far removed from what their worldview was. I remember going home and saying to myself, ‘Oh, why am I thinking so differently to what I would have thought in the past?’ I think that’s probably when I realised that my attitudes and my views had gone over to the other side [laughs].

Another participant’s initial learning outcome was to increase her knowledge about how adults learn, in order to rectify mistakes she had made and to learn what she was doing wrong. Clearly she began from a feared self-state, with high concern about getting the task right, which is common when teachers begin their career. Many reported awareness of a difference in their thinking about themselves as professional teachers: ‘I don’t know if I’ve done it or how it’s happened, but I’ve become defined by a qualification, a different person in my own right. I think differently; I think, I think differently.’ Another participant said:

How I view myself has also changed greatly. I am not apologetic when putting my opinions forward during staff discussions. The experience of studying has highlighted what I do know as much as what I don’t, and the balance is convincing me that I do know what I am talking about.

TEQ programmes for FET teachers must involve the whole person and cannot be separated out as a cognitive act or reduced to the application of skills or competences. Korthagen (2001) emphasises pedagogy of realistic teacher education that combines formal academic knowledge with perceptual knowledge that is personally relevant and supportive in enabling someone to understand their own behaviours in the light of beliefs, identity, and the values that underpin them.

Teaching is an enactment of the self in a holistic mix of academic and personal perceptual knowledge, skills, experiences, understandings, beliefs, and values. The development of a teacher’s identity is therefore strongly connected to a self-actualisation experience that ideally takes place in a transformative learning space where one feels safe and esteemed, and has trusted relationships and a sense of belonging socially.

This article has focused on two key areas:

The changes experienced by participants in their professional identity appear to have happened as a result of their learning during the TEQ programme. There was a general sense that changes were happening and that they were organic and incremental in the sector but occurring in tandem with the college experience. For participants, however, the changes experienced during their educational programme were more visibly focused and directed on their personal lives and professional practice.

Teaching Council recognition of FE teacher status had implications for work, career, and progression opportunities. This obviously relates closely to professional and situational dimensions of FET teacher role and identity, as they would now be on a par with mainstream teachers in primary and second-level education.

Our understandings of FET teachers’ evolving identity to date are general: they exist at some distance from the processes of people experiencing and behaving in particular work and study contexts. But none of them go to the core of what it means to be psychologically present in particular moments and situations that determine the driving force for the type of learning that underpins an evolving professional identity.

This is a critical factor in developing a different and fulfilling pathway towards professional development for FET teachers. Such probing relies on studying both people’s emotional reactions to conscious and unconscious phenomena, and the objective properties of jobs, roles, work, and professional development contexts, all in an FE setting. This article has shared some understanding of the variables influencing how FET teachers perceive themselves: identities, work roles, professional learning and development, and the relation between all three.

Coolahan, J. (2002) ‘Teacher education and the teaching career in an era of lifelong learning’, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 2. Paris: OECD . doi: 10.1787/226408628504

Entwistle, N. (2003) ‘Concepts and conceptual frameworks underpinning the ETL project’. Occasional Report 3, Higher and Community Education. University of Edinburgh: School of Education.

Graham Cagney, A. (2019) ‘“I am what I do”: Professional voices from the field of adult and further education’, in J.A. Gammel, S. Motulsky, and A. Rutstein Riley (eds.) I Am What I Become: Constructing an Identity as a Lifelong Learner. IAP Publishing.

Kegan, R. (2009) ‘What “form” transforms? A constructive-developmental approach to transformative learning’, in K. Illeris (ed.) Contemporary Theories of Learning. London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Korthagen, F.A. (2001) Linking Practice and Theory: The Pedagogy of Realistic Teacher Education. London: Routledge.

Markus, H. and Nurius, P. (1986) ‘Possible selves’, American Psychologist, 41(9), 954–969.

Mezirow, J. (1991) Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

O’Sullivan, E., Morrell, A., and O’Connor, M.A. (2002) Expanding the Boundaries of Transformative Learning: Essays on Theory and Praxis. New York: Palgrave and Macmillan.

Teaching Council of Ireland (n.d.) Registration of FE teachers. www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/Registration/.

Copyright © Education Matters ® | Website Design by Artvaark Design