This article presents stark evidence that the current practice of inclusion of children with autism in mainstream primary schools reflects a containment approach, and is maintaining the idea that being a ‘different’ learner requires a ‘special’ approach and environment.

In March 2018, Ireland ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN CRPD). A fundamental aspect of this Convention is to develop a respectful, inclusive education for people with disabilities among their non-disabled peers. Ireland, while late to the notion of inclusive education, is working towards and with the EPSEN Act, and has legislated for a concept of inclusion in education (Government of Ireland, 2004). The question of who needs ‘special’ education in an ‘inclusive’ setting has come to the fore, highlighted by the education needs of children with autism.

This article presents evidence of placement and educational experiences of children with autism that requires us to consider how inclusion is constructed and structured in our mainstream primary schools. It provides evidence of the stark reality that inclusion in practice reflects a ‘containment’ approach. Further, we are maintaining a concept that being a ‘different’ learner requires a ‘special’ approach and environment. This article argues that ethical sinkholes are created when there is little introspection on the ideology and practice of inclusion.

A research project to explore the literacy practices of children with autism in our mainstream primary schools required a ‘walk through’ seven schools across Ireland. It aimed to explore how children with autism engaged and showed their ability to participate and relate to a multimodal society in both school and community structures. It was immediately apparent that in Ireland we have created an intolerable phenomenon and need to have a conversation about our ideologies and practices for better inclusion outcomes for children with autism.

We have undoubtedly made a positive step towards supporting families in the education of their children with autism and other developmental disabilities. In 2017, one thousand special education classes were established to provide an appropriate education for children with autism (Banks and McCoy, 2017). In the space of only two years this figure has increased to 1,500, according to our education minister (McHugh, 2019).

Evidence from the National Council for Special Education (NCSE, 2018a) provides an estimate that 82% of special class provision is specific to autism support. Pressure for mainstream placement is again an issue. A news article recently drew attention to a lack of access to mainstream education, suggesting that some children are without a school place for the start of the school year 2019/2020 (O’Brien, 2019). Considerable government expenditure has been allocated to establishing special class provision for children and young people who have autism.

So it is time to ask, Are we doing the ‘right’ thing or doing things right? What constitutes inclusion for children with autism in our mainstream primary school system? Dillenburger (2012) asks a pertinent question: Why reinvent the wheel? We know what inclusion is. No matter what research, policy, or practice document you read on the topic, it will state clearly that inclusion is about:

So is this ideology of inclusion being achieved, or do we need to reinvent the wheel?

A starting point is to review what we mean by an inclusive environment. Legislation mandates an ‘inclusive setting’, but ‘inclusive environment’ is not clarified in the EPSEN Act. There is also a clause in the Act that recognises the need for appropriateness of setting where the identified needs of the child dictate an alternative environment.

An initial exploration of the term ‘inclusive environment’ leads us to think that it is purely a matter of architecture. It is well documented that children with autism may present with complicated sensory difficulties and learning styles and patterns that are different from others, and therefore they may require support to engage and participate in education and to be socially included.

Established primary schools are asked to take on an autism classroom in an endeavour to provide access to education for local children. Funding is provided and classrooms are attached to existing building structures. Schools being newly constructed are required to ensure that a ‘special’ classroom is created within the new structure.

One of the challenges for children with autism is language and communication, which presents as a substantial barrier to integration and participation in social life. An aim in education therefore is surely to scaffold and support engagement with peers in authentic social contexts. Contemporary thinking on childhood and autism must embrace the notion of identity as an evolving construction of the self through interactions and engagement with society.

The lived experiences of all children, regardless of ability or disability, reflect the evolving person. The design structures of autism classrooms around Ireland present a very challenging reality. Six of the seven schools in this project show how architecture can create and embed exclusionary practices and generate other social vulnerabilities for these children. The project also documents how the social and emotional needs of children with autism are not articulated in the design structures of these classrooms.

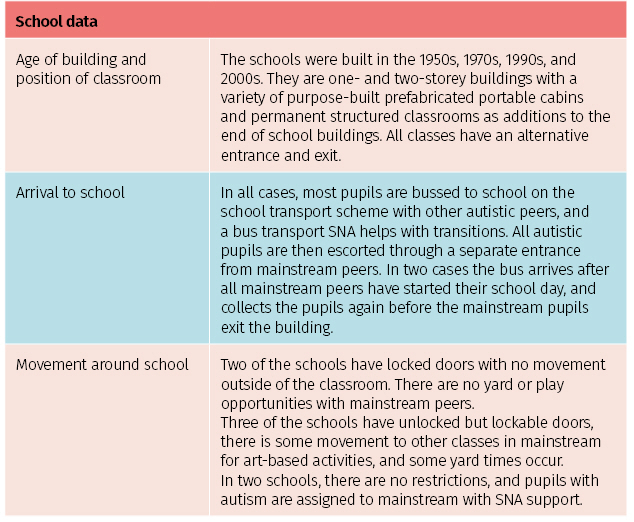

Young autistic people themselves have stated clearly in Goodall’s (2018) research that inclusion is about belonging. While children with autism may have specific challenges with sensory issues and self-regulation, this doesn’t warrant what Imrie and Kumar (1998, p. 365) call ‘back door treatment’. Table 1 below presents some realities for our consideration. When reviewing this table, ask yourself:

Table 1: Data from all schools in the project

Evidence from the physical structure and placement of the autism classrooms is vital to the conceptualisation of inclusion and inclusive learning. The physical separation observed in the structure of these autism classrooms appears to create a predetermined notion of the behavioural needs of autistic pupils and the general continued ‘normal’ function of the mainstream system.

The locked and lockable doors, while serving the ‘fright and flight’ traits of children in anxious or stress-related states, compound the ‘contained’ status of these children. It might be evident that we in Ireland are doing the ‘right’ thing in a ‘rights-based approach’ to bringing children with autism into the structure of the mainstream – but are we answering an appropriate ‘needs-based approach’? What is evidenced is that segregation remains a significant issue.

So are we doing things right in these segregated autism spaces? We should ask: How do children with autism benefit from education in these settings?

[ctt template=”2″ link=”Y53Qx” via=”no” ]In Ireland, we have created an intolerable phenomenon and need to have a conversation about our ideologies and practices for better inclusion outcomes for children with autism.[/ctt]

Evidence from empirical research has given us a justification for an autism theoretical approach to teaching and learning. We have learned that a strong understanding of the theories of autism enables us to make good decisions on curricula design and pedagogical approaches for each child diagnosed with autism (Baron-Cohen, 2008; Guldberg, 2010; Barton and Harn, 2012; Powell and Jordan, 2012; Conn, 2016). An eclectic approach is advised, and autism-specific approaches are evidenced in practice, such as interactive approaches (Dir™ Floortime), communicative approaches (PECS), integration approaches (LEAP), behaviour approaches (contemporary ABA), and discrete trial training (TEACCH) (O’Síoráin et al., 2018; Ring et al., 2018).

The investment in teacher education in Ireland for better outcomes for pupils with autism is a phenomenon in and of itself. In fact, Banks and McCoy (2017) suggest that 60% of the overall budget for special education in Ireland is spent on autism provision. The National Council for Special Education (NCSE) is inundated annually with applications from teaching professionals to upskill in the area of autism evidenced-based teaching and learning approaches. So:

Good autism practice promotes a pupil-centred approach to curriculum development, emphasising communication and interpersonal skills and the specific teaching of cultural norms and meanings. Functional skills are important but balanced with academic and life skills (Powell and Jordan, 2012, p. 21). Conn (2018) argues for ‘favourable interactional ecologies’, enabling children with autism to show capabilities and competences at tasks, using personal language constructs to build connections and understandings to their social situations. Physical activity and playful learning are essential elements in social and emotional learning.

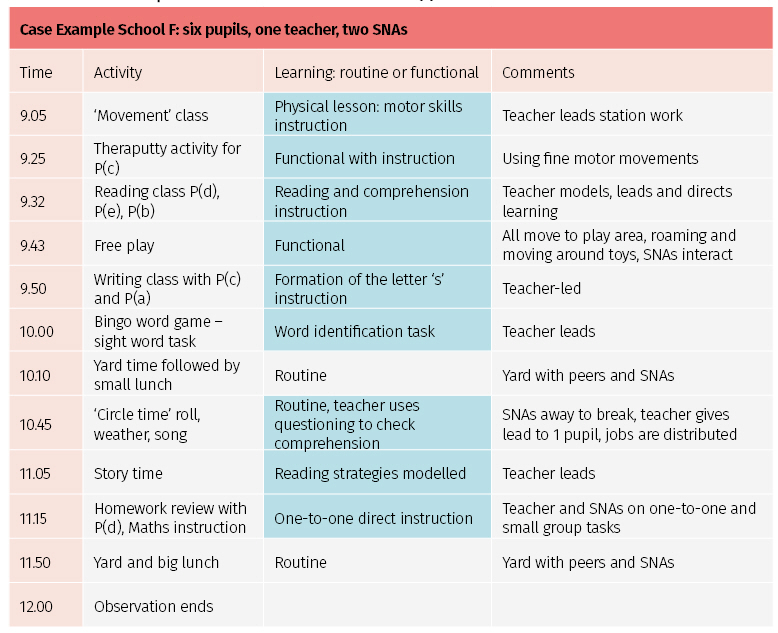

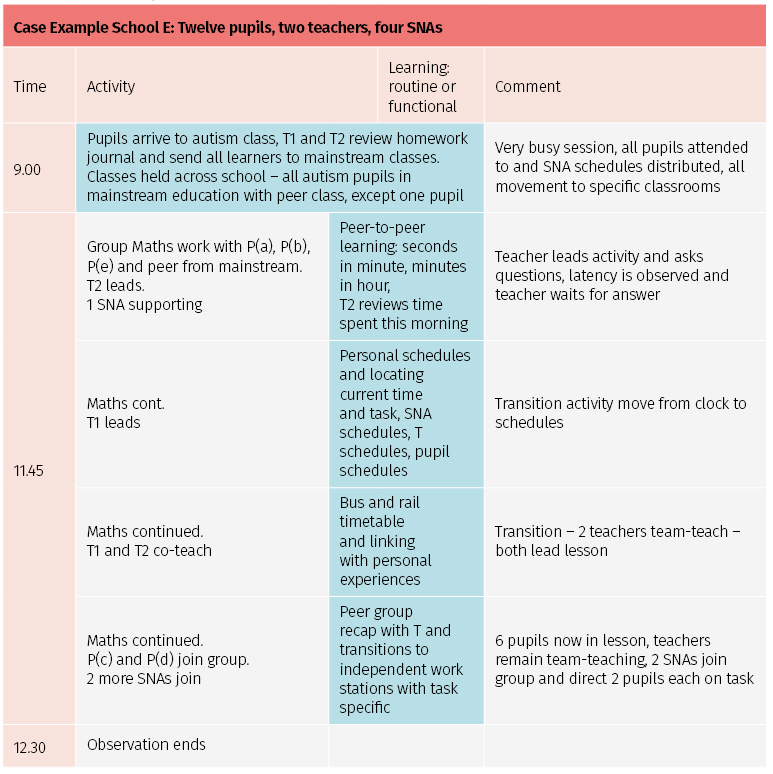

Tables 2, 3, and 4 below provide a snapshot of the observations of teaching and learning that took place in this research project. Three case examples are presented, with additional coding for anonymity of participants. When reviewing these tables, ask yourself:

The study recorded 27 hours of observations (9 hours in each term) across each classroom. The observation tool used was High Scope IEA Pre-Primary Project Observation Schedules (2007), Child and Adult Observation. The observations provided a view of the classroom schedule as the sessions rolled out.

Each case presented below is a snapshot of the use of time and an assessment of the tasks based on Powell and Jordan’s (2012) thesis that a balance of direct learning, life skills training, and functional activities is required in good autism teaching and learning. Observations provide evidence on direct teaching, functional activities, and general classroom routine.

Table 2: Case Example School 1 – Observation Term 2 (2)

Table 3: Case Example School 2 – Observation term 2 (2)

Table 4: Case Example School 3 – Observation term 2 (2)

From the tables above it is evident that inclusion is approached very differently across all three classrooms.

There is evidence in some autism classes that there is no movement of pupils outside of the class and that no social or play interactions occur with non-disabled peers. In fact, the lack of supported play and direct teaching indicates that little learning is experienced. Doing the same things in the same way, singing the same songs and engaging in the same actions daily does not promote new learning, thinking, or understanding of their social worlds. Significant teaching and social opportunities are lost in some case examples. There is evidence that little introspection on teaching and learning is occurring, and more significantly that an inappropriate concept of an inclusion approach is holding pupils in a confined space.

[ctt template=”2″ link=”pCHeX” via=”no” ]There is evidence in some autism classes that there is no movement of pupils outside of the class and that no social or play interactions occur with non-disabled peers.[/ctt]

What is the purpose of bringing learners with autism into this mainstream school? No interpersonal skills are being developed; no connecting to themselves, to their peers, or to the outside world is happening. Play as a free choice for children with autism is problematic, and evidence in this project posits the need to support and prompt play. Teachers in some cases were not observed as ‘play partners’, and opportunities to relate socially through play were lost (Theodorou and Nind, 2010). This approach to inclusion and autism is creating greater vulnerabilities for these children, their parents, and the community at large.

In some autism classes there is a focused approach to teaching and learning, and the pupils experience a variety of learning in groups among their fellow autism classmates. Language and communication skills are being taught but at a very low level, and opportunities for ‘free talk’ and conversation starters are minimal; this has implications for interpersonal skills development. The teaching tasks are action-based and reflect the academic learning needs of the group. The pupils do get to play with non-disabled peers during break times, but there was no evidence of structuring play and playful experiences to enable the pupils to engage with peers and learn social rules.

Teaching and learning in some settings are very intense, with six tasks occurring in an hour. Pupils are well settled and transition well between tasks, enabling the teacher to engage learners in high levels of learning. However, questions arise. Why are learners not moving into mainstream for academic work? Why are mainstream learners not coming to learn alongside these learners? How is the construction of ‘special’ part of inclusion in this school? Could a review of pupils’ growing capabilities change the function of this classroom over time?

[ctt template=”2″ link=”34k1_” via=”no” ]The social and learning needs of children with autism are not articulated in the design structures of these classrooms, and the lack of opportunity to develop a sense of belonging is compounding difference.[/ctt]

In one school all pupils are supported in learning in their mainstream class and return to the autism classroom for specifically targeted lessons to enable them to remain in mainstream at a good social and academic level. Team teaching is evidenced, and the use of scheduled SNA movement means that higher levels of support are available as the lessons and tasks increase in complexity. Teacher time is well spent on direct teaching and management of learning. Pupils in this school gain a sense of belonging, because they exist in the mainstream mindset of all teachers and pupils. A can-do attitude exists, and children with autism are enabled to gain the soft skills or key competencies (McGuinness, 2018) necessary for twenty-first-century living.

This research project proposes that segregation remains a significant issue for a significant number of pupils with autism in mainstream education. The findings indicate clearly that the structure of the classrooms and positioning of the units happen before pupils enrol, and therefore set in motion a persistent negative expectation for problematic behaviour associated with autism. The social and learning needs of children with autism are not articulated in the design structures of these classrooms, and the lack of opportunity to develop a sense of belonging is compounding difference.

The evidence from this project suggests that some children with autism are limited in their literacy practices and learning experiences by the bounded nature of the ‘autism’ built environments and by ‘autism’ teaching and learning. This project calls for an urgent national collaborative focus on supporting teachers in autism classrooms to reflect critically on inclusion ideologies and practices for better pupil engagement and social learning opportunities. ‘Inclusive practices’ without introspection create exclusion and other vulnerabilities for autistic learners.

Banks, J. and McCoy, S. (2017) ‘An Irish solution…? Questioning the expansion of special classes in an era of inclusive education’, Irish Economic Review, 48(4), 441–61.

Banks, J., McCoy, S., and Frawley, D. (2017) ‘One of the gang? Peer relations among students with special educational needs in Irish mainstream primary schools’, European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33(3), 396–411.

Banks, J., McCoy, S., Frawley, D., Kingston, G., Shevlin, M., and Smyth, F. (2016) ‘Special classes in Irish schools, phase 2: A quantitative study’. Trim: National Council for Special Education.

Baron-Cohen, S. (2008) The Facts: Autism and Asperger Syndrome. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barton, E. and Harn, B. (2012) Educating Young People with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, National Association of School Psychologists.

Conn, C. (2016) Play and Friendship in Inclusive Autism Education: Supporting Learning and Development. Oxon: Routledge.

Conn, C. (2018) ‘Pedagogical Intersubjectivity, autism and education: Can teachers teach so that autistic pupils can learn?’, International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(6), 594–605.

Daly, P., Ring, E., Egan, M., Fitzgerald, J., Griffin, C., Long, S., McCarthy, E., Moloney, M., O’Brien, T., O’Byrne, A., O’Sullivan, S., Ryan, M., and Wall, T. (2016) ‘An evaluation of education provision for students with autism spectrum disorder in Ireland’. Trim: National Council for Special Education.

Dillenburger, K. (2012) ‘Why reinvent the wheel? A behaviour analyst’s reflections on pedagogy for inclusion for students with intellectual and developmental disability’, Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 37(2), 169–80.

Goodall, C. (2018) Inclusion is a feeling, not a place: a qualitative study exploring autistic young people’s conceptualisations of inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1523475

Government of Ireland (2004) The Education of Persons with Special Educational Needs Act (EPSEN). Ireland: Stationery Office.

Guldberg, K. (2010) ‘Educating children on the autism spectrum: Preconditions for inclusion and notions of “best practice” in early years’, British Journal of Special Education, 37(4), 168–74.

Imrie, R. and Kumar, M. (1998) ‘Focusing on disability and access in the built environment’, Disability and Society, 13(3), 357–74.

McGuinness, C. (2018) ‘Research-informed analysis of 21st-century competencies in a redeveloped primary curriculum’. NCCA Final Report, May 2018. www.ncca.ie/media/3500/seminar_two_mcguinness_paper.pdf.

McHugh, J. (2019) Special Educational Needs Staff. Dáil Éireann debate, 22 January 2019. www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2019-01-22/28/.

Mitchell, D. (2014) What Really Works in Special and Inclusive Education: Using Evidence-Based Teaching Strategies, 2nd ed. Oxon: Routledge.

NCSE (2018a) Joint Committee on Education and Skills: Provision of ASD and Special Classes in Mainstream Schools. In Houses of the Oireachtas (October, 2018) Joint Committee on Education and Skills. Report on the Provision of Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD) and Special Classes in Mainstream Schools. 34/ES/14. https://data.oireachtas.ie/ie/oireachtas/committee/dail/32/joint_committee_on_education_and_skills/reports/2018/2018-10-25_report-on-the-provision-of-autistic-spectrum-disorders-asd-and-special-classes-in-mainstream-schools_en.pdf.

NCSE (2018b) ‘Educational experiences and outcomes of children with special educational needs: Phase 2 – from age 9 to 13’. Trim: National Council for Special Education.

O’Brien, C. (2019) ‘Not going to school next week: “Our children are slipping through the cracks”’. Irish Times, 24 August. www.irishtimes.com/news/education/not-going-to-school-next-week-our-children-are-slipping-through-the-cracks-1.3994081.

O’Síoráin, C.A., Shevlin, M., and McGuckin, C. (2018) ‘Discovering gems: Authentic listening to the voice of experience in teaching pupils with autism’. In: B. Mooney (ed.) Ireland’s Yearbook of Education 2018–2019. Ireland: Education Matters.

Powell, S. and Jordan, R. (2012) Autism and Learning: A Guide to Good Practice. London: Routledge.

Ring, E., Daly, P., and Wall, E. (2018) Autism From the Inside Out. Oxford: Peter Lang.

Theodorou, F. and Nind, M. (2010) ‘Inclusion in play: A case study of a child with autism in an inclusive nursery’, Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 10(2), 99–106.

Copyright © Education Matters ® | Website Design by Artvaark Design