In the modern world, specialised but inflexible thinking will no longer do. We are no longer preparing students for lifelong careers in specific areas. A new curriculum design at Trinity College Dublin gives students a chance to see beyond the intellectual confines of their chosen disciplines.

Third-level education in Ireland has traditionally required students to specialise early in a specific subject, or sometimes two, and to focus largely on this area throughout their years in college. The goal has been to develop deep domain expertise. At Trinity College Dublin this has always involved an emphasis on research-led teaching. Students are taught by faculty who are active researchers in their fields, and they are not just exposed to the corpus of knowledge in the field but trained in the methods used to acquire and evaluate it.

The objective is to go beyond just teaching students about the subject matter of, say, economics, history, or genetics: to also teach them how to work and think like an economist, a historian, or a geneticist. Even if the student does not go on to a career in that field, the exposure to the deep workings of a given domain and the requirement to engage at that level of intellectual rigour cultivate the transferable skills of critical thinking that are so valuable in any enterprise.

This can come at a cost, however. Thinking like an economist, a historian, or a geneticist is fine – those are hugely powerful and successful approaches to their respective domains. But they are not the only ways to think about the subjects that concern each discipline. The danger in a highly specialised education is that students will develop too narrow and blinkered a perspective, that their ways of thinking will be worn into certain tracks or ruts – the same tracks and ruts that each discipline has been in for decades.

In the modern world, such specialised but inflexible thinking will no longer do. We are no longer preparing students for lifelong careers in specific areas. The average time spent in any job is now under five years, and many of our graduates will go on to jobs that currently do not exist. They will need intellectual agility and adaptability to succeed in the workplace. They will need to be able to see a problem from multiple perspectives, and to work with people with varied expertise.

Indeed, all of us, as a society, will require the talents and perspectives of people from diverse disciplines, working together to solve the many challenges now facing us, such as climate change, an ageing population, and the threats of populism.

The challenge for educators is to balance the need for deep domain expertise with the need to expose students to thinking from other disciplines. This is actually a battle against the increasing specialisation of academia in general. A research-led education has to take students all the way down to the coalface – that’s where new discoveries are dug out, where we’re excavating new facts or ideas.

You’d like to think those nuggets of knowledge would be transported back to the surface, where larger theories could be created, out in the light – that we’d all come back up once in a while to show everyone else what we’ve discovered. But in reality most theory-building goes on down in the mines. The further down we all go, the further away we get from each other.

Indeed, many disciplines have been separated for so long that they have built up not just their specialised body of facts but their own traditions and styles for building theories, implicit premises and shared assumptions, and accepted ways of doing things and thinking about things. When we bring new students down the mine with us, we are giving them the chance to become domain experts, but we are also subtly indoctrinating them.

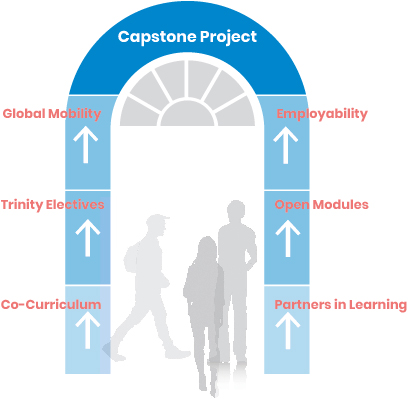

The Trinity Education Project, currently in its final year, aims to renew the undergraduate experience at Trinity College Dublin, with a commitment to balancing depth and breadth. Students will still receive a research-led education in their chosen discipline, culminating in a capstone research project – an independent piece of work designed to engage students in the scholarship and research methods of their field.

[ctt template=”2″ link=”4UsgQ” via=”no” ]At Trinity College Dublin, students are not just exposed to the corpus of knowledge in the field but trained in the methods used to acquire and evaluate it.[/ctt]

But along the way, we have introduced more opportunities for students to lift their heads up and look around – to take modules from other disciplines, to follow their own interests, and, within a structured framework, to define their own curriculum. There are three ways in which students can avail of these opportunities.

First, students who enter in a single honours pathway will now have the chance to take up a new subject in second year. If they choose, this subject can be continued through years three and four, so that the students can graduate with a minor award in that new subject and a major award in their primary discipline. In their first year, students will learn more about the variety of subjects available to them, enabling them to make an informed choice, even for subject areas that might have been obscure to them as school leavers.

Second, across all our programmes in the faculties of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, and of Science, Engineering, and Mathematics, students will also have space in the curriculum to take a number of Open Modules. These are modules delivered by another discipline, but considered complementary to a student’s primary subject areas. For example, a student in Biosciences might take a module in Physics, Geology, or Science Communication. A student in Economics can take modules in Business, Politics, or Sociology. Students in History can take modules in English Literature, Law, Islamic Civilisations, etc. Students in each subject area will have a wide range of Open Modules to choose from and can pursue whatever topics most appeal to them within this offering.

And finally, all students will have the opportunity to take at least one of a new set of modules called Trinity Electives. These are a flagship feature of our new undergraduate curriculum, designed to bring together students from across all disciplines to study topics that are related to the main research themes of the university or to important societal challenges. These modules will take a multidisciplinary approach to the topic, allowing students to see the question from multiple perspectives and to approach it with diverse methodologies.

The topics of the Trinity Electives are wide-ranging and diverse, such as: Cancer – the Patient Journey; The Art of the Megacity; The EthicsLab – Responsible Action in the Real World; Energy in the 21st Century; Design Thinking; Irish Landscapes – Interdisciplinary Perspectives; and many others, including introductory modules to many different languages and cultures.

[ctt template=”2″ link=”Kp6aQ” via=”no” ]The danger in a highly specialised education is that students will develop too narrow and blinkered a perspective.[/ctt]

For the faculty involved, Trinity Electives present a unique chance to interact with their colleagues in other disciplines, to explore the real-world impacts of various aspects of their research, and to introduce their favourite topics to students from all areas of the university. Indeed, the idea has sparked tremendous creativity from faculty members across all disciplines, with exciting new proposals being made all the time.

For the students, these three options for breadth will give them a chance to emerge from the mine and look around, explore new subject areas, pull together ideas in their own minds, and see connections that might otherwise go unnoticed. But beyond the specific facts and ideas that they may learn about, a deeper pay-off is exposure to a range of intellectual perspectives.

Critical thinking – that most prized transferable skill – cannot be effectively taught as a topic in its own right, divorced from specific contexts. It is gained through deep immersion in a discipline and the expectation that students will develop professional levels of rigour and analysis. But that exclusive approach can leave a gap, an intellectual blind spot: the inability to be critical of the most fundamental assumptions of the discipline as whole.

Every discipline has its own perspective and a set of shared, often implicit assumptions. These are useful, maybe even essential, in allowing progress within a shared framework. But they can also place fundamental limits on seeing solutions to certain types of problems – ones where the conceptual framing of the field is simply inappropriate or incomplete. When working paradigms become unquestioned dogma, true creativity is stifled.

By the time we have dragged students to the coalface, they’ll have specialised so much that they will have assimilated these core paradigms and shared assumptions, to the point where they not only don’t question them, they no longer recognise them as such. In that way, perspectives are like accents – you may not realise you have one yourself, until you hear somebody else’s.

This is where a bit of intellectual travel can be such a consciousness-raiser. Our hope is that these new features of our undergraduate curriculum will foster a mindset of curiosity and confidence and help to cultivate the attributes of truly independent thinking, ethical awareness, effective communication, and continuous intellectual development that are core to a Trinity undergraduate education.

Copyright © Education Matters ® | Website Design by Artvaark Design