As we enter the final decade of action on achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and struggle to respond to global challenges, learning about global citizenship issues has never been more important. This article provides an overview of the place of the SDGs in post-primary education and of the response by Education and Training Boards Ireland (ETBI) to supporting its schools to engage in teaching and learning about education for sustainable development throughout the school environment.

The concept of sustainable development is not new and has undergone many iterations and changes of emphasis over the last few decades. More recently, the Brundtland Report (1987) provided an ‘official’ definition and in its simplest form proposes that ‘sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (p. 41). The current application of this definition comes in the form of the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Signed into being in August 2015, these Global Goals were for the first time historically adopted by all 193 member states of the UN.

The seventeen Goals, aimed at ending poverty, reducing inequality, and tacking climate change, by 2030, are underpinned by a set of 169 targets. These targets provide not only a formal mechanism for achieving the goals but also a measure of their progress and success, by giving a detailed list of specific challenges while also supporting engagement on a more personal level. While the Goal aligned to Climate Change (SDG 13) has gained much prominence in recent years, the agenda for collective engagement and action is clear. Despite certain challenges seeming more urgent, the aspiration for success must be channelled collectively through all the Goals – engaging in a partnership for progress.

While the vision for the SDGs was negotiated at an international level, the objectives and targets need to be enacted and achieved at national and even local level. It is this potential for local action that set the seed for engagement with sustainable development education within the Education and Training Boards (ETB) sector.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development contained a pledge that ‘no one will be left behind’ (UN, 2015, p. 1), and while it is seldom disputed in principle, in practice it presents many challenges. Student activism, particularly the climate strikes, has been evident both in Ireland and globally over the last number of years. Taking to the streets as part of an organised outcry, these young people force us all to reflect on the future of our planet. However, representative does not necessarily mean inclusive, and it is important that all our students in all our classrooms be presented with an opportunity for engagement. This engagement can take many formats and may not necessarily result in strikes or public demonstrations. It is this principle of inclusion and the belief that no one should be left behind that underpins the basis for the development of the Take 1 Programme.

With the mission of inclusivity at its core, the aim of Take 1 is to promote ETB schools as Sustainable Development Goal schools, providing a programme of awareness-raising about all seventeen Goals, encouraging the linking of formal and non-formal activities relating to the Goals and supporting schools to work towards including the SDG agenda in their well-being programmes. When the Take 1 Programme launched and training commenced in October 2019, Covid-19 had not yet raised its head in Ireland, but there were many other challenges to introducing another intervention into an already busy school environment.

[ctt template=”1″ link=”Awc5z” via=”yes” ]“Each day-long training provides an overview of the SDGs, analysis of where schools are at in relation to sustainable development education, and planning for integration at classroom and management level.[/ctt]

Taking account of these challenges, Take 1 works towards developing activities which sit within the curriculum by providing real and operable engagement underpinned by school needs. Key to its success is not only to make the data about the seventeen goals available and understandable, but to highlight how embedding teaching and learning about the Goals can potentially be aligned to already existing learning outcomes.

In its first year the focus was primarily but not exclusively on the Junior Cycle curriculum, offering school leaders the opportunity to engage with contemporary issues that are currently challenging our young people and teaching staff. Training delivery replicates the model operated by ETBI, requiring the attendance of a principal or deputy in combination with the interested teachers, reflecting the key messages of many of the policy approaches of the education sector. This explicit commitment to collaborative and creative improvement across the school environment is supported by educational research which notes that school leadership is considered the second-greatest influence on student learning, second only to teacher effectiveness (Leithwood & Riehl, 2003).

The issues and information encompassed by sustainable education are wide-ranging and potentially complex, often informed solely by media headlines. The Take 1 model engages schools, students, and teachers in a flexible learning approach, ensuring that schools can adopt and adapt the programme as a built-in model which can be sustained as it grows. Each day-long training provides an overview of the SDGs, analysis of where schools are at in relation to sustainable development education, and planning for integration at classroom and management level.

Resources shared with attendees replicate the information from the training sessions and provide a mapping plan for the Junior Cycle curriculum. This mapping analysed the syllabus for each Junior Cycle subject, highlighting where content is already aligned to sustainable development and the SDGs and ensuring that additional content sourcing is kept to a minimum. This alignment to learning outcomes reflects the core principle of inclusion by offering the learning to all students in all class groups.

Students from Coláiste an Átha, Gorey.

Take 1 Week, December 2019.

Following initial training, participants were encouraged to explore opportunities to put the approach into practice through one or more subject areas. This work was then showcased during Take 1 Week (2–6 December) and promoted using visuals, photographs, and activities, shared on social media with the hashtag #ETB_SDGS. Subsequent data analytics showed the breadth and range of engagement showcasing SDG learning in fifteen subject areas across schools throughout the ETB sector.

This analysis also provided information on the flexible approach used by different schools. In the formal curriculum, one school chose to concentrate on SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), using case studies to explore the gender pay gap and issues of economic growth in their Business Studies class. This learning was supported by a visit from a guest speaker, Kevin Hyland, who had been pivotal in leading efforts to include text on human trafficking and modern slavery in the transcript of the original SDG agreement. All these activities mapped to the learning outcomes in Strand 3 of the syllabus.

Students from Griffeen College, Lucan, learn about

SDGs over lunch during Take 1 Week.

Other formal applications included the use of recycled materials to make prototypes in Engineering classes, while Home Economics students investigated the impact of food choices from ecological and ethical perspectives (LO 1.15) and applied sustainable practices to the selection and management of food and material resources (LO 1.16) (NCCA, 2017, p. 15). These learning outcomes not only are formal aspects of the syllabus but also align to several SDGs, which can be referenced throughout the learning: SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

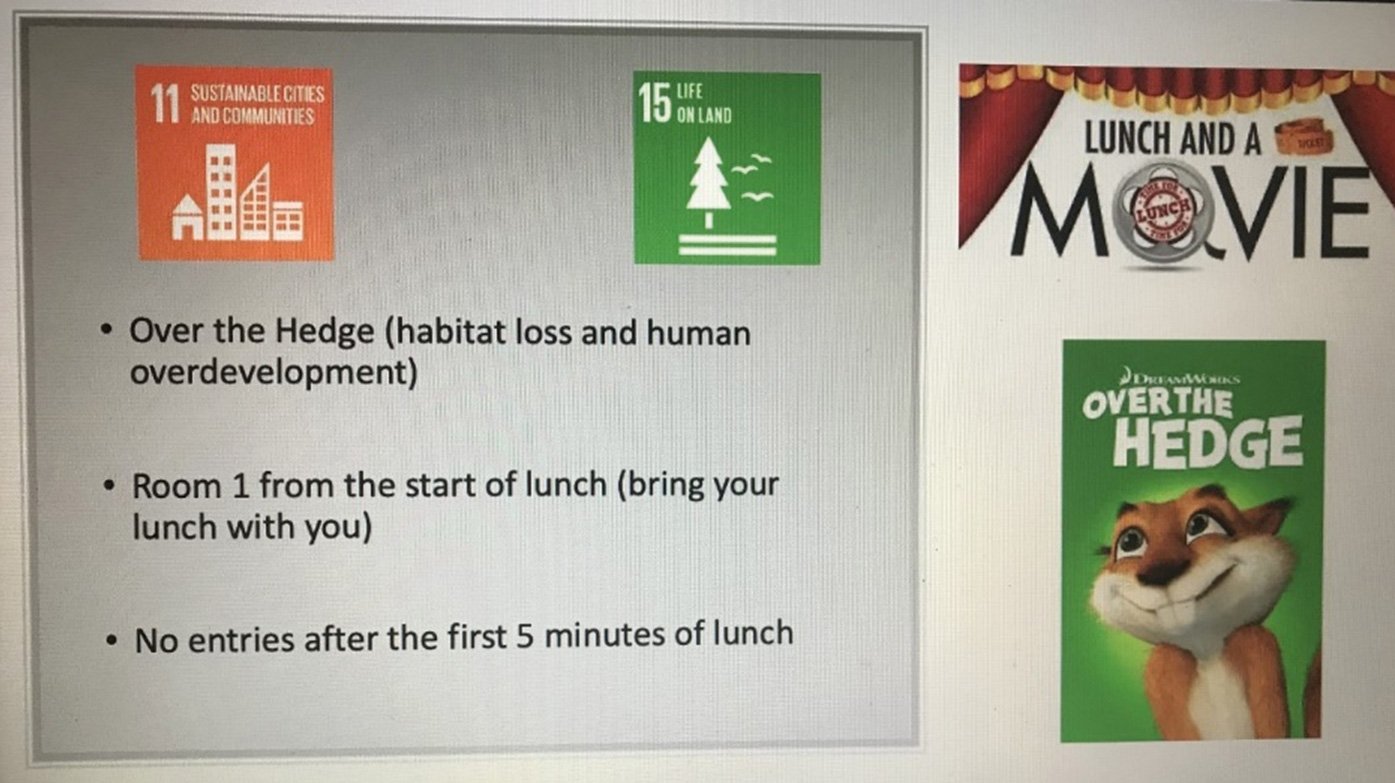

Schools also engaged in learning about the SDGs in the non-formal and extracurricular space by selecting relevant books and films for lunchtime club activities, planting a school garden, collaborating with local volunteer organisations, and using recycled materials to make gifts for the Christmas market. Where several teachers engaged in activities during Take 1 Week, awareness was raised through the entire school community, across several subjects, inside and outside the classroom, with capacity for engagement by all.

The visual and verbal feedback showed strong evidence of the ease with which learning about SDGs can be integrated into the school environment. Providing a resource that maps the learning outcomes to the SDGs ensures that each teacher has the relevant alignment to hand, and at a minimum only needs to highlight how the existing content already encompasses sustainable development elements. It also supports a move away from, but not exclusive of, the notion that sustainable education teaching and learning are addressed only through subjects like Geography and Civic, Social and Political Education.

This embedded approach acknowledges and embraces the importance of learning about all seventeen SDGs and how their interconnected nature is vital for their continued impact and success. While addressing issues of climate action (SDG 13) and climate justice may seem to be the more public face of students’ concerns, for a student already grappling with issues of hunger and poverty (SDG 1 and SDG 2), addressing issues of climate justice might not be their immediate priority. It is equally important to explore and understand how working towards achieving one Goal can have an impact on many others.

Aligning the SDG key themes to the core values of ETB schools

There is also an opportunity to demonstrate how the Global Goals and their aspiration for inclusion reflect the core values of the ETB sector. As part of the initial preamble to the introduction to the SDGs, five key area reflect the overall themes of the sustainable agenda: People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnership. These ‘five Ps’ present a more inviting comprehension of sustainability, while also aligning with the core values of ETB schools: Excellence in Education, Respect, Care, Equality, and Community. This natural association supports the sector in making connections to voice support for the Global Goals, to make decisions that advance them, and to take actions to help with their implementation.

The Take 1 Programme also takes cognisance of national policy in both the education and sustainable development arenas and aims to align with existing objectives and aspirations. Goal 1 of the Action Plan for Education 2019 supports a quality learning experience ‘so that learners can respond to the changing opportunities they will face in the future’ (DES, 2019, p. 16). Embedding learning about sustainable development and global citizenship, as a natural extension of the curriculum, supports this future-proofing. Similarly, Take 1 attends to the proposed awareness-raising aspiration of the SDG National Implementation Plan (2018–2020) as well as key areas of Education for Sustainability: The National Strategy on Education for Sustainable Development in Ireland 2014–2020 (DES, 2014).

An interim report on progress in 2018 commended the work done to date but also noted that the ‘lack of system-wide awareness of the strategy must be rectified and further action must be taken to communicate, raise awareness of and embed ESD [Education for Sustainable Development]’ (DES, 2018, p. 44). It is clear that despite many of these well-placed interventions, practice on the ground does not yet fully reflect policy objectives.

At school level, the framework document Looking at Our School 2016 is designed to ‘support the efforts of teachers and school leaders, as well as the school system more generally, to strive for excellence in our schools’ (DES Inspectorate, 2016, p. 5). Leadership and Management (Domain 1) encourages the promotion of a culture of improvement, collaboration, innovation, and creativity in learning, teaching, and assessment, while the statements of practice in Teaching and Learning encourage teachers to value and engage in professional development and professional collaboration.

[ctt template=”1″ link=”he8ov” via=”yes” ]“Schools that are beginning on their sustainable-education journey can be supported and mentored by schools that are further along.[/ctt]

The Take 1 Programme model of training – teacher and leader learning professionally and then sharing that learning at school level – will add value to all levels of leadership practice. Looking at Our School also highlights the value of students as active agents in their learning who engage purposefully in a wide range of learning activities and respond to learning opportunities. The Take 1 Programme, in responding to contemporary issues, supports schools in assuming responsibility for education which is explicitly learner-centred while valuing and reflecting student voice. While impact and change may be varied, the intention to be responsive and current should be viewed as highly valuable in the school community.

ETBs are well placed to operate towards a collaborative approach in their sector. Each ETB has a director of schools who has a role in the leadership of teaching and learning in schools, and this coordinating role provides a natural cohesion to the work of individual schools. Schools that are beginning on their sustainable-education journey can be supported and mentored by schools that are further along, and this model can be enhanced by the work of each school feeding into the work of each ETB, which can be shared across the network of sixteen ETBs. The various forum and network groups already in operation in this sector provide a wealth of embedded experience throughout the system.

While the first year of the Take 1 Programme made a significant impact, there is enormous potential for further growth both within and outside the sector. Resources are being developed to reflect the syllabus content and learning outcomes of the Senior Cycle curriculum, including the Leaving Certificate Applied. At either end of this spectrum, the Goodness Me Goodness You Programme in ETB Community National Schools presents an ideal opportunity to embed Take 1, while the further education arena provides capacity to develop the learning through education, apprenticeship, and training modules. The training programme will continue to grow, offering opportunities for new participants while also supporting skilled practitioners to continue to build on their learning.

Take 1 Week will be celebrated again on 23–30 November 2020, when we hope to witness the continued growth of sustainable development education for all members of our school communities.

Take 1: Year in review

REFERENCES

Brundtland Report (1987) Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Department of Communications, Climate Action and Environment (DCCAE) (2018) The Sustainable Development Goals National Implementation Plan 2018–20. Dublin: DCCAE.

Department of Education and Skills (DES) (2014) ‘Education for Sustainability’: The National Strategy on Education for Sustainable Development in Ireland 2014–2020. Dublin: DES.

Department of Education and Skills (DES) (2018) ‘Education for Sustainability’: The National Strategy on Education for Sustainable Development in Ireland – Report of Interim Review. Dublin: DES.

Department of Education and Skills (DES) (2019) Action Plan for Education 2019. Dublin: DES.

Department of Education and Skills Inspectorate (2016) Looking at Our School: A Quality Framework for Post-Primary Schools. Dublin: DES.

Education and Training Boards Ireland (ETBI) (2020) Journal of Education, 2(1): The Sustainable Development Goals in Education. www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/63575156/etbi-journal-of-education-vol-2-issue-1-june-2020.

Leithwood, K.A. and Riehl, C. (2003) What We Know about Successful School Leadership. Philadelphia, PA: Laboratory for Student Success, Temple University.

National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) (2017) Junior Cycle Home Economics. Dublin: DES.

United Nations (UN) (2015) Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. (A/Res/70/1). New York: UN.

Copyright © Education Matters ® | Website Design by Artvaark Design