This article looks at what kind of research is being carried out at present and what ethical issues need to be considered in doing research in a pandemic. It focuses on the interview as a method of data collection and the inherent challenges that Covid-19 presents for researchers.

On 12 March 2020, when all educational institutions closed due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the pause button was pressed for many research projects because face-to-face fieldwork was no longer possible. Researchers had to reset and rethink their research designs and approaches. The formal learning environment at all levels was transformed overnight, moving out of classrooms, lecture halls, and other such settings to a home-based, online space, a new and potentially very challenging experience for learners, teachers, parents, and others.

Many questions were being asked: What will this mean for education and the experience of learning and teaching at all levels? What will it mean for the role of the teacher, the student, the parent or caregiver, the policymaker, the lecturer, the leader, boards of management, and the communities who were impacted? How will it affect individuals? How will structural inequality play out in this new space? Policymakers were grappling with how to react. This dynamic situation has provided a vital and unprecedented space for education researchers to explore, examine, and evaluate the educational impacts of the pandemic.

All social and educational research has an ethical dimension and can be fraught with challenges at the best of times. Undertaking research in educational settings during a global pandemic presents additional issues in data collection, such as participant recruitment, informed consent, data management and storage, and balancing burdens and benefits. Research ethics should be at the forefront of every study undertaken at this time, in order to protect the health of participants, researchers, and wider communities and to ensure that our research is relevant and contributes to understanding these complex contexts.

Social Research Ethics Committees (SREC) review research projects that involve human participants and personally identifiable information about human beings to ensure that the proposed research is ethically sound and does not present any risk of harm to participants. In Maynooth University we saw a surge of applications during the past six months for new research and amendments to planned projects.

To begin, we will present some general ethical issues and then look at what kinds of research are being carried out at present, with particular focus on the interview as a method of data collection.

Kiely and Heavin (2020) coined the term ‘covidata’ to describe the insatiable need and demand for data being driven by the pandemic. This demand is causing fatigue for some participants, who face repeated requests to participate in research (Dempsey and Burke, 2020). Participants’ environments have changed, and it is important to consider that some may be suffering health anxiety, may be ill or have been ill in recent weeks, may be looking after loved ones, or may be living in homes where they do not have control over their own privacy.

Darmody, Smyth, and Russell (2020) list over twenty-two published reports up to July 2020 of Covid-19-related research from primary and second-level education. Research should be conducted within an ethic of respect for the person, knowledge, democratic values, the quality of educational research, and academic freedom (BERA, 2018). This ethic of respect needs to be kept to the forefront in a time of intense research activity; researchers must be mindful that all social science should aim to maximise benefit and minimise harm, and at a time like this we should focus on reciprocity in our research. For some, having their voice heard is important and can be beneficial for participants.

The big change for researchers was in completing fieldwork. This was not possible to do face-to-face during lockdown. The move to online data collection presented many challenges, such as identifying potential participants, access and making contact, informed consent, confidentiality, and duty of care. It also provided opportunities to explore more creative ways to work with participants.

Alternatives to face-to-face interviews and focus groups

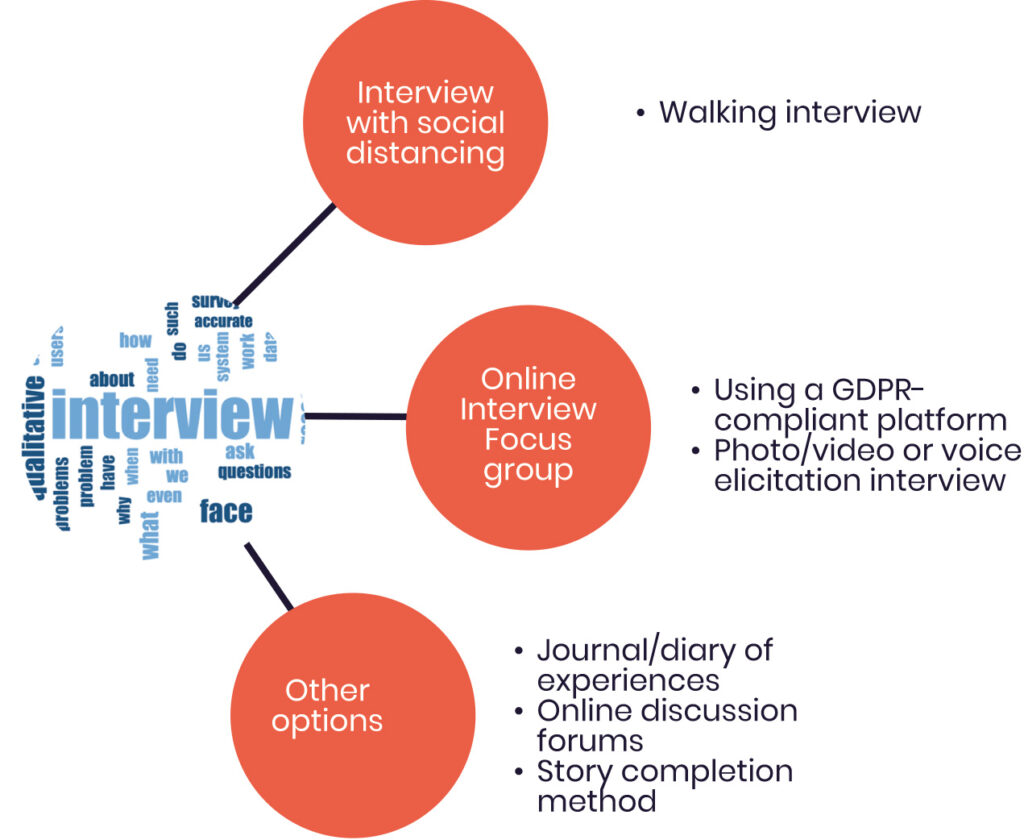

Qualitative research is intimate because there is little distance between the researchers and their study participants. Covid-19 has meant that this distance is now less than intimate. It has required a change to how we carry out fieldwork. The diagram presents some options that researchers are using in place of face-to-face interviews and observation.

Some educational researchers who cannot visit classrooms on site due to Covid-19 restrictions have opted to use video recording. The same issues of confidentiality exist in the online space, with some additional issues of where the videos will be stored and where personal images may be used. Others have opted to carry out audio-recorded walking interviews, where a two-metre distance can be maintained.

Another method involves asking participants to use a camera or voice recording app (often on their smartphone) to take photos, make videos, or voice memos about their everyday practices and interactions that they can then share with the researchers in response to questions or prompts. In this instance one must guard against taking any images or sound files that include participants who have not given consent to be in the research. It is imperative to password-protect all data, transfer it to an encrypted device, and to remember not to share paper copies, pens, and so on.

It is normally expected that participants’ voluntary informed consent is obtained at the start of the study, and that researchers will remain sensitive and open to the possibility that participants may wish to withdraw their consent for any reason and at any time (BERA, 2018). These principles apply to children and young people as well as to adults.

[ctt template=”1″ link=”QC6Kx” via=”yes” ]“The move to online data collection presented many challenges… it also provided opportunities to explore more creative ways to work.[/ctt]

Researchers using online interviews need to negotiate informed consent in this space. It is important to consider the multiple layers of consent that might be needed, such as parental and teacher consent, young people’s assent, and the potential gate-keeping role of the school principal or board of management in providing access to participants. A photographed or scanned signed consent sheet can be used.

Researchers should do everything they can to ensure that all potential participants understand, as well as they can, what is involved in a study. They should be told why their participation is necessary, what they will be asked to do, what will happen to the information they provide, how that information will be used, and how and to whom it will be reported. They also should be informed about the retention, sharing, and any possible secondary uses of the research data.

Equally, from an ethical perspective, researchers need to consider if participants might experience any distress as a result of their participation. Giving potential participants an indication of the sorts of questions they might be asked can help them decide if they want to participate. Consider whether you need to provide an appropriate point of referral in case of distress, such as a guidance counsellor for students. This information can be provided on an information sheet sent to the participants and should be in language appropriate to the person’s developmental level.

Subject to the requirements of legislation, including the Data Protection Act (2018) and the Freedom of Information Act (2014), researchers should protect the confidentiality of research participants. Researchers have a responsibility to ensure that participants understand the extent of anonymity and confidentiality offered at all stages of the research, from data gathering to dissemination. Participants should be apprised of the limits of confidentiality.

The device on which the interview will be recorded needs to be secure and password-protected. If conducting interviews on platforms such as Teams or Zoom, it is important that both the researcher and the participant ensure they are in a private room, where their interview cannot be compromised by a third party listening in.

Researchers have a responsibility to discern the most relevant and useful ways of informing participants about the outcomes of the research in which they were or are involved. In the spirit of openness, this means we need to think about reporting our research through the channels people use, including online media, virtual convenings, and academic papers. As we respond to and recover from this pandemic, it is important that our research be part of the solution and augment people’s lived experiences.

REFERENCES

British Educational Research Association (BERA) (2018) Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. www.bera.ac.uk/.

Darmody, M., Smyth, E., and Russell, H. (2020) The Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic for Policy in relation to Children and Young People. Dublin: ESRI.

Dempsey, M. and Burke, J. (2020) COVID-19 Practice in Primary Schools in Ireland Report: A Two-Month Follow-Up. Maynooth: Maynooth University.

Kiely, E. and Heavin, C. (2020) ‘What are the ethics around research during a global pandemic?’ RTÉ Brainstorm. www.rte.ie/brainstorm/2020/0511/1137702-research-ethics-coronavirus/.

Copyright © Education Matters ® | Website Design by Artvaark Design