In March 2019, the distinguished educationalist John Hattie flew into Dublin and gave an energetic presentation at the NAPD’s annual symposium, tackling teacher efficacy, raising standards, using the evidence in critical evaluation, and making learning visible. Derek West reports from the event.

John Hattie, Professor of Education and Director of the Melbourne Education Research Institute at the University of Melbourne, Australia.

The energetic John Hattie roadshow swept into the Radisson Blue Hotel at Dublin Airport in March 2019. Hattie presented an upright, austere figure in front of the packed audience. He was hard-edged, with high expectations both of us and for us. He cut to the chase from the get-go, wanting to ‘focus on the core attributes, the processing attributes that make learning visible and that make schools successful’.

For Hattie it was all about the clear identification of these attributes. He showed hearty contempt for ‘peripheral attributes’ such as class size, resources, finance, and buildings. He was intent on making learning visible to the students, ‘such that they learn to become their own teachers’. The persistent theme was to keep learning at the forefront of thought and to consider teaching primarily in terms of its impact on student learning.

Know thy impact! And what works best is the impact of leaders.

From time to time, we were invited to join in the conversation, but only in short bursts. Hattie and his colleagues had too much to tell us and not enough time. This was literally a flying visit, hence the location. Hattie had hit the ground running, meeting with Harold Hislop, chief inspector at the Department of Education and Skills, and some senior DES officials for breakfast, going straight on to the symposium, with a packed hall, and then – with barely time to say goodbye – on to a plane and off to the next gig. Every moment had to count, and the task was to consider the core business of schools.

Building teachers’ collective efficacy is Hattie’s aim: not only how to capture the expertise but how to identify what it constitutes, and to ruthlessly discard any definitions or ideas that are not germane to the core concept. He spent the day raising the bar, with no time for soft thinking or self-congratulation.

Hattie was, however, complimentary at the outset. His whistle-stop research on the Irish education system (this was his first visit, so how much can you learn over breakfast?) left him impressed by standards of achievement and our 92% retention rate. But he was not going to let the assembled leaders bathe in complacency. Like the art critic John Berger, who was mentioned, Hattie favours fresh ways of seeing and the high-end standards we should be aiming at.

[ctt template=”2″ link=”3V50d” via=”no” ]He put it to us that schools had to be ‘inviting places’: more attractive, more accessible; places where children wanted to come to learn.[/ctt]

He exuded some of the pugnaciousness of the ‘Aussie’, such that we felt obliged to listen to him. He was there not to charm but to challenge, and to change the debate from ‘what works’ to ‘what works best’ and even then the best was not to be regarded as good enough.

Hattie grappled with the word ‘achievement’ but wanted to dig deeper than a cosmetic notion of success. He put it to us that schools had to be ‘inviting places’: more attractive, more accessible; places where children wanted to come to learn. It’s not about school being a comfort zone, where familiar learning is rehearsed. Rather, children want to be challenged; they need it. Why come to school to learn what you already know?

Hattie rattled off ideas like bullets, confronting cosy notions about:

His put-downs were acerbic. And all the time there was analysis based on research, and the frame was a representation of effectiveness of all the sacred cows of education in hard, cold percentages. What makes for effectiveness? What doesn’t? Here we had to accept unpalatable facts about the things that we thought were actually working.

[ctt template=”2″ link=”r4fvD” via=”no” ]Change the debate from ‘what works’ to ‘what works best’ and even then the best was not to be regarded as good enough.[/ctt]

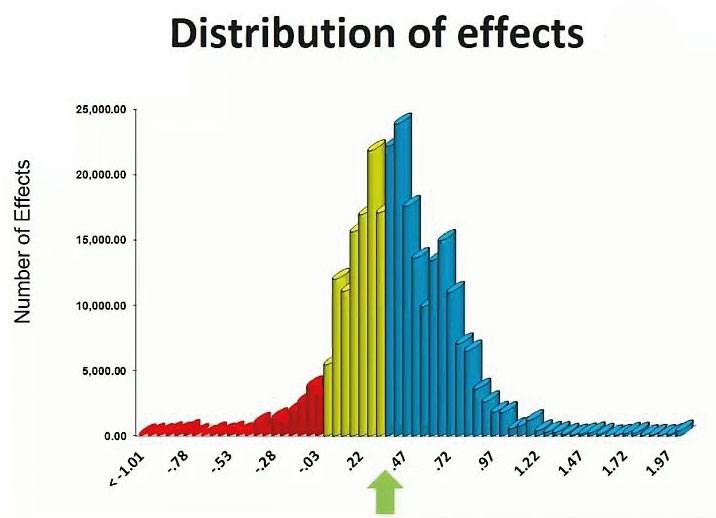

‘Almost any intervention can stake a claim to making a difference to student learning,’ Hattie says. But he demands that we look closely at the evidence about the extent to which it enhances learning. Most effects are minuscule, and he wants to focus on what really works. Setting the bar at zero is ‘so low as to be dangerous’. Improvement needs to be at least 0.40 (the average) to be considered worthwhile – that’s the ‘hinge point’. By Hattie’s calculation, about half of classes achieve 0.40 or above; half are below. The bar is too often set at zero, which means we’re in grave danger of thinking we don’t need any changes in our system.

Poet Charles Causley has his anarchic schoolboy Timothy Winters ‘shoot down dead the Arithmetic bird’; Hattie, armed with research outcomes, meta-analyses, and studies was able to shoot down dead a lot of the things we take for granted. He questions our concept of achievement and criteria he finds irrelevant.

Distribution of effects

Among the most important purposes of education, he says, ‘is the development of critical evaluation skills, such that we develop citizens with challenging minds and dispositions.’ Critical evaluation – for students, teachers, and leaders – is a core notion in Hattie’s thinking. He describes it as the complete opposite of assuming things. It’s about ‘the importance of evidence to counter stereotypes and closed thinking, to promote accountability of the person as responsible agent, and to vigorously promote critical thinking and the importance of dissenting voices.’

At the start of his presentation, Hattie left us to ponder a slide titled ‘Distribution of ‘Effects’ (see image), with shades that ranged from excellence to incompetence. The red line is below zero; the orange zone requires some change; the blue zone is good.

Effect size (d) is the core term used by Hattie; d = 0.40, the average effect size, is the critical measure. So when he looks at homework and finds that the average d over five meta-analyses of homework is 0.29, he concludes that the effect of homework overall is below an acceptable average. While it varied with school level, the overall average is below the mega-average. This figure should prompt us to look at ways of doing homework more effectively. Don’t abandon it, but try different approaches.

‘When teachers and schools evaluate the effect of what they do on student learning,’ he observes, ‘we have visible learning inside’ – learning that is the explicit and transparent goal. It is teachers seeing learning through the eyes of the students, and students seeing teaching as the key to their ongoing learning.

The teachers in the blue zone need to keep doing what they’re doing, but they also need to be part of a coalition to work across the school. Hattie asked us if we had the courage to identify the teachers in each zone. Had we the courage to identify where we are on that spectrum? Throughout the morning, he hounded us to think straight and deep. The only consolation he offered was to suggest that, based on his whirlwind appraisal of our system, we are 60–70% in the blue zone. Phew!

[ctt template=”2″ link=”kQu11″ via=”no” ]He is particularly virulent in his attack on the creeping amateurism – teaching aides and parents who muscle in and end up doing most of the work for the kids.[/ctt]

He digressed to talk about his involvement in what he calls ‘the dark side’: the political side of education in Australia. In 2014 he was appointed chair of the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). Through this role, he can provide national leadership in promoting excellence, so teachers and school leaders have maximum impact on learning. His mission is to persuade education ministers in Australia’s eight states that the key target for resources should be teaching standards. He rejects out of hand the term ‘proficient’ as applied to teachers; he sees it as a negative term and demands that we go much, much further.

Teachers are not comfortable with this, lest it place too much credit – and potentially blame – on them. Hattie feels that too much of the resourcing of education is misplaced. He is particularly virulent in his attack on the creeping amateurism – teaching aides and parents who muscle in and end up doing most of the work for the kids. This does not bring us into the blue zone.

Teachers’ mind frame is critical – their view of their role as teacher and as an evaluator of the effects of their actions. Hattie continually stresses the importance of evidence-based methods but says it is also important to accept that there is no one hard and fast method. Variation is a huge factor, and learning is a very personal journey. ‘Almost everything works. All that is needed to enhance achievement is a pulse,’ he says. He argues that we should attain, at a minimum, gains of at least or above the average for all students.

[ctt template=”2″ link=”2f7FW” via=”no” ]Hattie is big on the value of trust and the maximum benefits of effective feedback.[/ctt]

We have to develop an ability to recognise learning, to understand how it works, and to recognise multiple ways of learning and accept that there are diverse ways of doing this. How does one learn? We struggle with the language of learning in our attempts to make it visible. But there is a sequence – engagement, processing information, and using errors (the ‘Goldilocks principle’) as opportunities to learn. Hattie is big on the value of trust and the maximum benefits of effective feedback.

John Hattie gave us a mesmerising morning. If he set out to make our brains hurt, he succeeded. His philosophy of learning is based on a vast amount of research, involving thousands and thousands of student responses. He left us wanting more – and of course, the more is available in his new book, which was central to the other, more promotional presentations by his colleagues Julie Pitt and Stephen Cox.

Pleased with the outcomes of the day at the Radisson Hotel, Dublin Airport: Harold Hislop, DES Chief Inspector at the Department of Education and Skills; John Hattie, Professor of Education and Director of the Melbourne Education Research Institute at the University of Melbourne, Australia; Kieran Golden, President of the NAPD

Copyright © Education Matters ® | Website Design by Artvaark Design