The pandemic has serious implications for child poverty. There are lessons to be learned from the last economic crash, when child poverty in Ireland soared at the fastest rate in Europe. Will history repeat itself, or will the Irish state take the necessary measures to protect its most vulnerable children? This article explores the issue through the lens of one DEIS school in Dublin.

Over the past decade, Ireland has had one of the sharpest decreases in early school leaving in the EU, going below our national ET2020 (Education and Training 2020) target of 8% and the EU target of 10% (Donlevy et al., 2019). The impact of the Covid-19 lockdown threatens to dismantle this progress.

A first major concern is the impact on child poverty of the economic crisis generated by Covid-19 and the series of lockdowns. There is a clear lesson to be learned from the previous economic crash after the banking crisis. Between 2008 and 2011, child poverty soared in Ireland at the fastest rate in Europe.

The AROPE indicator (‘at risk of poverty or social exclusion’) is the share of the population who are either (1) at risk of poverty, meaning below the poverty threshold, (2) in a situation of severe material deprivation, or (3) living in a household with a very low work intensity.

From 2008 to 2011, the AROPE for children rose in twenty-one EU member states. According to Eurostat, the largest increases in AROPE since 2008 were in Ireland (up 11 percentage points up to 2010) and Latvia (10.4), followed by Bulgaria (7.6), Hungary (6.2), and Estonia (5.4). In other words, in the last economic crash, Ireland placed the burden of poverty most substantially on its children – more than any other country in Europe. Far from being an inevitable consequence of the recession, this was a clear policy choice.

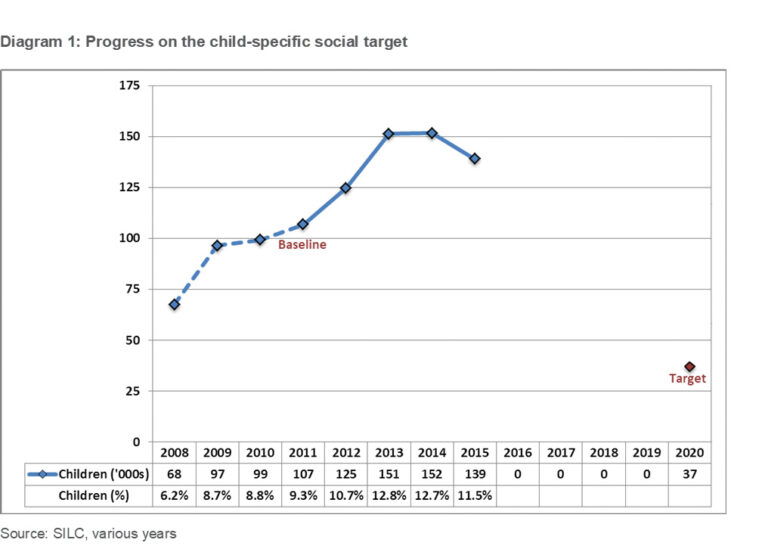

Equally concerning are the official child poverty statistics from the Irish Department of Social Protection, which show the extensive acceleration of child poverty between 2011 and 2014 (see diagram).

While there were some improvements in child poverty rates in 2017 and 2018, the question now arises as to whether history will repeat itself – or will the Irish state take proactive efforts to protect its children from the poverty impact of the recession induced by the pandemic?

One promising indication that a different policy response to child poverty will take place in this decade is the explicit commitment in the Programme for Government 2020 to ‘Continue to review and expand the roll-out of the new Hot School Meals initiative’. This vital initiative has been followed through in the October 2020 budget commitment of an additional €5.5 million for hot meals in schools for 35,000 more children nationally.

However, there needs to be a much more substantial financial commitment to expand this across DEIS (Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools) and other schools nationally, so that it is not simply a hit-and-miss approach depending on which schools can or cannot avail of this national scheme. There is also the issue of hot meal provision for families in poverty and outside of school times, such as holiday periods. This all needs to be part of a wider national strategic approach to face up to the crisis of child poverty in light of Covid-19.

The pandemic is exacerbating the trauma and adversity impacting on the mental health of our children and young people, including the additional emotional and financial strain of lockdown on so many families. This requires heightened awareness among policymakers about a strategic gap in supports in Irish schools that puts Ireland out of step with many European countries: the lack of emotional counsellors or therapists in and around every school.

A recent report on early school leaving, published by the EU Commission, recognises that ‘Emotional counselling and support is provided in a range of countries in order to help those suffering from serious emotional distress, including the Czech Republic, Belgium and Germany’ (Donlevy et al., 2019). It also notes: ‘In France, all pupils have access to the Psychologist of Education for psychological support and career guidance. Emotional counselling is also available in Sweden, where all students have access to a school doctor, school nurse, psychologist and school welfare officer at no cost and in Slovenia.’

The report highlights:

In some countries, emotional counselling is expressly backed by legislation. In Poland, legislation mandates for the existence of a system of support to students who are having significant difficulties at school, in the form of one-to-one academic tutoring and psychological support where required. … In Denmark, legislation states that school leaders can choose to recommend a student for pedagogical-psychological assessment, the results of which may initiate a process where the student may receive psychological support. Croatia and Bulgaria also have legislation in place that provides for emotional counselling and psychological support.

Emotional counselling and therapeutic supports, such as play and art therapy, need to be available in all DEIS schools, and arguably beyond, to provide at least one key limb of support against the mental health strain and trauma experienced by so many of our children. Ireland is radically out of step with many European countries who provide these services in schools.

This is not addressed by the National Educational Psychological Service (NEPS) or by career guidance increases, because neither one provides or is suitable to provide ongoing individual therapeutic supports for trauma and complex emotional needs. The teacher as ‘one good adult’ in the government’s Wellbeing Policy Statement and Framework for Practice (2018) is no substitute for qualified emotional counsellors or therapists.

Many DEIS schools provide play therapy, but this is ad hoc, funded by a mixture of corporate sources, some limited School Completion funding, or voluntary therapeutic placements. Now is the optimum time for the Department of Education and Skills to fund a much-needed service for children. Play and art therapy and emotional counselling supports can build on the Draft Programme for Government’s commitment to ‘Improve access to supports for positive mental health in schools’ and would be a fitting post-pandemic legacy for our children.

In Dublin’s North East Inner City, at least 25% of children in primary schools did not engage in distance learning. From speaking to school principals, we know this is the case across DEIS schools and is even higher in certain areas. From conversations with parents, we know there is a myriad of reasons for non-engagement, including parents not coping with a child’s behaviour, or poor parental mental health. Some children have parents with addiction issues and are in the care of grandparents who may not be tech savvy.

Every school is different, and every school experience is different. Even across the ten schools in the North East Inner City, the demographics vary greatly. This piece captures one school at a moment in time. The most striking aspect of the return to school is that the children are really delighted to be back and have settled in very well after being out of their routines for so long. As we contemplated the return, this had been our biggest concern. The smooth transition is testament to the teachers who work in DEIS schools, who are keenly aware of the significance of the pupil–teacher relationship.

We were fortunate in Rutland NS to experience no staff turnover this year. There was minimal movement of teachers across schools – a positive impact of Covid-19 – so every teacher kept their class. This ensured a relatively seamless transition, as the focus was on reconnecting and refamiliarisation, rather than September’s usual time spent establishing relationships with a new group of children.

Since the reopening, the segregation of classes on yard has vastly improved behaviour. Children whose behaviour on yard is less than ideal tend to gravitate towards similar children in another class yard, leading to inter-class conflict. Yard supervision is one of the most challenging aspects for teachers, particularly senior yard, where tempers can easily fray during football matches and arguments can erupt. This often has a knock-on impact on the classroom, as teachers can spend time after yard attempting to sort out inter-class issues, which takes from curriculum time.

Restorative practice, an evidence-based programme which is extremely worthwhile, is something we are attempting to introduce, but it is time-consuming. Reducing the potential for conflict is huge. This reduced stress for the teachers has a positive impact on their mental health.

For the children, too, having to stay with their own class is beneficial. Typically very vulnerable children with poor social skills gravitate towards the familiarity of siblings on yard and can be reluctant to make friends. With the new changes, they have to make friends.

It is too soon to make any academic pronouncements, but a few observational trends are apparent from class teachers, who tell us that in senior classes (fourth to sixth) there is a noticeable gap between those children who engaged in online learning during the closure and those who did not. The precise impact of this is not yet measurable. In the junior classes, the gap seems to be more attributable to the differences already evident between the children rather than to engagement during closure, but again it is early days.

Across the board, there are concerns about the reduction in children’s concentration and stamina levels. Regression in fine motor skills, namely handwriting, is also prominent; the nature of online learning means that these skills were under-utilised during the closure. Many children now need to rebuild their physical fitness after a more sedentary existence. Much of this is attributable to children spending more time online – playing computer games, using social media, and so on.

It will take time to fully recalibrate the skills necessary for the more traditional forms of learning in the classroom. Next May/June, when the annual standardised tests are completed, is when the true nature of the impact of closure on children’s learning will become apparent.

REFERENCES

Donlevy, V., Day, L., Andriescu, M., and Downes, P. (2019) Assessment of the Implementation of the 2011 Council Recommendation on Policies to Reduce Early School Leaving. Commissioned Research Report across 35 countries for EU Commission, Directorate General, Education, Sport, Youth and Culture. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Copyright © Education Matters ® | Website Design by Artvaark Design